This is the second article in a four-part series on Swannanoa School in New Zealand. Start here.

This is the second article in a four-part series on Swannanoa School in New Zealand. Start here.

Swannanoa, like other schools in New Zealand, is expected to build strong relationships with the local iwi (tribe) as part of its accountability to the community and for upholding the Treaty of Waitangi. The Ngāi Tahu iwi has helped to write a cultural narrative for the school, a process that helps deepen the relationship to the land and grounds the Swannanoa school community in the Māori culture.

This is one of the hardest things I think for Americans to understand. Even though it’s located in North Canterbury with one of the highest proportions of Pākehā (European) communities — the school is approximately 90 percent Pākehā — biculturalism means that the students and the adults in the school system have a sense of their New Zealand heritage as both indigenous and as immigrants. Obviously, not everyone shares this belief in NZ, and some are outright antagonistic to the idea of biculturalism. However, schools as public institutions have a responsibility to uphold the Treaty of Waitangi and to contribute to creating a bicultural nation.

Two years ago when principal Brian Price arrived, the framework for learning (called Aspire) had run its course. Price made it clear that Aspire had a lot of value but there was little ownership or reference to the framework in day-to-day life. It had become a picture on the website but not a living, breathing vision of learning. There were limitations to the Aspire vision as well. It emphasized academic achievement without attention to well-being and did not make any connections to the Māori culture. Price noted, “The Aspire framework could have been from any country. There was nothing that rooted it in New Zealand or the New Zealand experience.” The Education Review Office audit had called for a 3-year audit and called for more attention to cultural responsiveness, building relationships with students, and accelerating learning. (Please note: A 5-year audit reviews suggest that schools have all the core aspects of a high performing school in place.) Thus, one of the first steps Price took was to renew the vision and values. Price explained, “We had to start with values. What you focus on flourishes. We needed to create a culture to support the shift to personalization.”

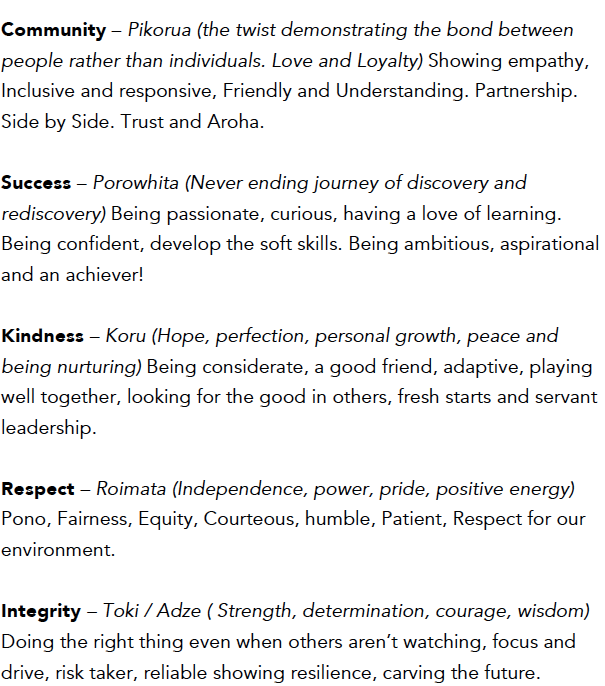

Drawing upon the ancestors’ travels to the Arahura River on the western coast to gather the sacred pounamu, or green stone, Swannanoa embraced the concept of Taonga (treasure) to introduce their values. Each value or touchstone — community, success, kindness, respect, and integrity — is described using English and Māori.

Each of the touchstones can be found on posters as well as small sculptures throughout the the Swannanoa campus. The concept of Taonga or treasure is also used to talk about students: “Each one of the children at Swannanoa is a Taonga.”

As always, the Māori concepts have somewhat different meaning. Reflecting on the nuances between Māori and Pākehā concepts helps to better understand both cultures. As Price explained to me the history of the greenstone trail and the importance of creating a culture that draws from both Māori and Pākehā, he pulled out his pounamu from under his shirt, explaining, “Pounamu is to be gifted to you and worn close to the heart.” And there went any interest on my part of purchasing a piece of pounamu jewelry for myself: I will have to wait until someone gifts the sacred stone to me.

Price shared a bit about his personal story in learning about and embracing Te Reo Māori and the culture. “Fifteen years ago I didn’t know anything about Māori culture except ‘kia ora,’” he said. “As I’ve learned more about Māori culture, I’ve learned more about community. I’ve learned more about leadership.” He described that in the Pākehā culture, the concept of belonging is important but it often assumes a dominant culture that everyone else has to adapt to. In comparison, he explained, “There is a Māori saying of ‘I am allowed to sing my song.’ This suggests the sense of belonging and also respect. We want a school culture where every student can sing their song.”

Price described that as a country, New Zealand is in the infancy of biculturalism. Often, schools use Māori words in their vision and value statements without bringing in the full meaning, the soul, of the concepts. I had heard this concern from several Māori education leaders as well. Integrating Māori phrases is an important to link to the Māori cultural heritage but it shouldn’t end there.

Honoring Māori culture is integrated into most if not all of the products of the Ministry of Education. Reaching up to grab the Teaching Council’s Code of Professional Responsibility and Standards for the Teaching Profession from his bookshelf, Price pointed out examples of how cultural responsiveness was included in the core expectations for teachers. As I tried to understand what it has meant for schools to honor the Treaty of Waitangi, Price provided concrete examples. Cultural responsiveness begins with a robust and active demonstration of respect. Students are expected to learn Te Reo Māori and the Ministry of Education would intervene if a school that failed to teach Te Reo Māori. Shouting or anything that could be perceived as bullying by teachers is not tolerated. (I highly recommend Culture Speaks by Russell Bishop to understand the experience of Māori students in English-medium schools.)

Next, Price opened a well-read copy of Tū Rangatira: Māori Medium Educational Leadership and Kiwi leadership for principals: principals as educational leaders. Both reports provide guidance on leadership, one rooted in Māori culture with an eye to ensuring Māori students thrive, while the other is rooted in Pākehā culture. He pointed out differences between the two documents, “Tū Rangatira speaks to the role of guardianship in leadership. As leaders, principals need to be thinking about the cultural and spiritual level of caring for children as well as the well-being of adults in the school community. Kiwi leadership is about you as an individual, whereas Tu Rangatira is about community.” Noting that the Ministry often produces two different documents, one for English-medium and one for Māori-medium schools, he re-emphasized, “I draw on Tū Rangatira for leadership guidance even though only 10 percent of the students are Māori. What is good for Māori learners is good for all learners.”

As we wrapped up our conversation, I asked Price whether he thought Māori culture was influencing the education system in general. He reflected for a moment before explaining, “In the Pākehā culture, we turn to science. We can also turn to spirituality as well. There are many way that Māori culture enriches our school. It helps us understand well-being for the community as well as for the individual. It also offers concepts and rituals that are not found in Pākehā culture. For example, we have learned to handle bullying and conflict differently by understanding and drawing upon Māori forgiveness rituals. This helps us nurture and strengthen relationships. Of course, we want to pay attention to how individual children are doing. But we can also pay attention to how we are doing — students, teachers, and parents — as a community of learners.”

For anyone visiting New Zealand, it’s worth taking the time to review the following resources:

- Treaty of Waitangi

- Te Marautanga o Aotearoa: He Whakapākehātangam the English translation of Te Marautanga o Aotearoa, the Curriculum for Māori-medium schools.

- Tū Rangatira: Māori Medium Educational Leadership

- Ka Hikitia, the Ministry of Education strategy for accelerating learning for Māori and Pasifika students.

- Tataiako: Cultural Competencies for Teachers from Teaching Counsel

Read the Entire Series