This is the fourth article in a four-part series on Swannanoa School in New Zealand. Start here.

The team at Swannanoa School understand that learning starts with engaging and motivating activities. As we walked through the campus, principal Brian Price was bubbling over with enthusiasm, pointing out the goats, native plantings bed, produce store, and bee and butterfly garden. All of these and more are part of the Seeds of Learning program to link the school to the lives of students in this semi-rural community. I asked if they were related to project-based learning. Price replied with a firm no. “It’s important to have high engagement activities for students to explore that are not always related to formal learning,” he said. “We want students to come to school. We want activities that resonate with them and their lives. This is even more important if learning is challenging for students.” It was clear that at Swannanoa they understand the difference between engaging activities and high quality project-based learning — and that both are important for different reasons. (See conversation with Bob Lenz, Buck Institute, about high quality project-based learning.)

As teachers began to plan and develop activities and units that take into consideration how to reach all students rather than using one prescribed curriculum, they pay more attention to the needs of students who are struggling as well as those who are performing at higher curricular levels. In addition, each hapū created specific tracking processes including tracking boards with the names of students, information on their progress including assessment data, and the interventions being tried to help them move forward. The name of students are often color-coded according to their home room teacher. Every teacher in the hapū is aware who needs special attention or help staying on task.

Accountability Rests in the Hapū

Price emphasized, “Everything depends on the shared accountability of the hapū. We believe in the power of three. Three teachers working together create a dynamic professional learning community and accountability. Teachers need the collaborative working environment to problem-solve and access different perspectives. They need to know the students and see how they respond to different conditions and strategies. It helps to have several teachers able to tap into their full range of knowledge and approaches.” He then emphasized, “This only works if there is a trusting and safe environment for educators. If they feel safe, then they can create a safe environment for kids.”

A teacher in her first year of teaching shared her experience with collaborative teaching. “It’s a powerful model for new teachers. If I don’t understand something I can ask immediately. I can observe other teachers. I can’t think of a better way to learn how to be a teacher. And each teacher brings strengths so you can tap into a much wider set of knowledge.”

I asked about organizing with multi-age bands and whether having teachers stay with students more than one year has made a difference. Price responded, “Multi-age helps us stay focused on students and their point of challenge rather than delivering one curriculum. In addition, given that students in each Year (in the US we would say grade) are all at different points along the curricular levels, it is much easier to do flexible grouping around points of challenge with different teachers pulling students together as needed.” He also warned, “Looping, or keeping one teacher together with a group of students for more than one year, is too risky. What if the teacher is new or ineffective? What if there is some type of mismatch between the student and teacher? It’s just too dangerous. The collaborative teaching is absolutely essential for being able to be responsive to every student.”

Working as a team, hapū teachers meet formally twice a week to talk about how their students are doing and what adjustments need to be made. Price explained, “Let’s say you have seventy kids in your hapū. How many are not where they should be? There may be three with special needs who need to have individualized approaches to make sure they are making gains. There may be another seven where we don’t know why they aren’t progressing. In those situations, we need to be working closely with the family. We need to be asking ourselves if there is more we can do to be culturally responsive. It may be that we need to reach out more, check in more, and find ways to make the learning even more engaging. We may need to find out what is important to the student. We can give special awards. And we need to find out who is important to the child. It might be the uncle’s mate visiting the school who might make the difference.” Price paused, “All that matters is that we find out what will make sure each student wants to learn.”

Learning Requires Creating Safe Environments

Price and the team of teachers at Swannanoa believe that it is critically important to create a safe environment for kids. A teacher explained, “Part of the growth mindset is about understanding how the brain works and how to become better learners. Students also need to understand that it is fine to fail. We worry about the Generation Alpha kids. It’s important that they learn resilience and how to persevere in face of challenges. That means they are going to need to fail sometimes and pick themselves up and keep trying.” This point is made over and over on the walls of the schools with posters with quotes about risk, failure, and perseverance from famous New Zealanders.

Swannanoa uses several strategies for creating a safe and inclusive culture. There is a coffee shop, supported by a local family, in the school for parents and community members to stop by and chat with neighbors and teachers. Profits are given to the school. The Seeds of Learning program mentioned earlier in this article helps to make connections between the school and the home lives of children, most of whom live on small farms although at least one parent is also likely to have a full-time job.

Price pays attention to making sure teachers feel safe as well. The New Zealand practice of mid-morning tea helps. Every school I visited had large, open rooms with kitchens and plenty of seating around small tables, couches, and comfy chairs. Every day, all teachers come together at the same time for a cup of tea, a nibble, and socializing. If there are any formal announcements, they are kept to a minimum. The goal of tea time is respect for the hard work of teaching and an opportunity for relationships to grow.

Price pays attention to making sure teachers feel safe as well. The New Zealand practice of mid-morning tea helps. Every school I visited had large, open rooms with kitchens and plenty of seating around small tables, couches, and comfy chairs. Every day, all teachers come together at the same time for a cup of tea, a nibble, and socializing. If there are any formal announcements, they are kept to a minimum. The goal of tea time is respect for the hard work of teaching and an opportunity for relationships to grow.

Price noted that shifting from a hierarchical model of leadership to a Marae Leadership model (a form of distributed leadership) demonstrates respect for teachers and staff throughout the school. He said, “We want to make sure schoolwide policies and operations work to support the teachers and the students. We have someone from each hapū participate in schoolwide reviews and problem-solving.”

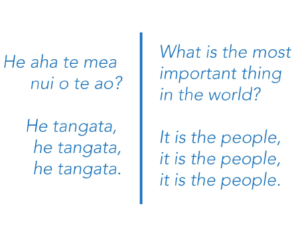

It all comes down to the school motto — What is the most important thing in the world? It is the people, it is the people, it is the people. Learning happens where safety, respect, trust, and relationships flourish.

Read the Entire Series