One of the key features of a competency-based system is a transparent framework of learning. Every school making the transition takes the time at some point in their transition process to build shared understanding of either a competency framework or the state standards. (Please note: Many schools do this right a way which can be helpful but it also leaves room to think that competencies are just a different word for standards. Other schools start with laying a ground work of the Building Blocks of Learning such as social-emotional skills or with clarifying their pedagogical principles.) Clarifying the expectations for learning through a competency framework includes building understanding of what depth of knowledge the standards are set at to align instruction and assessment, as well as building a shared understanding of what proficiency looks like for the grade level being taught (in addition to the standards above and below that students might need to or are ready to tackle).

However, in most cases, these transparent competency frameworks are primarily organized within a school or perhaps across a district. Only a handful of states have developed a full K-12 competency framework. And as far as I know, there is no place (yet) where higher education has been willing to construct a transparent framework that might extend from K-13 or even K-16.

Thus, there is both inspiration and insight to be gleaned from New Zealand’s nearly seamless and highly transparent framework of achievement objectives and qualifications. (See the previous article looking at Key Competencies.) There are essentially three overlapping structures that connect from Year 1 (our kindergarten) all the way through the tertiary system of post-secondary education and training. Below is the best I was able to understand of this framework organized around performance levels. However, I remain confident that there are plenty of nuances that I didn’t catch. If anyone sees errors in my description, please let me know and I will correct.

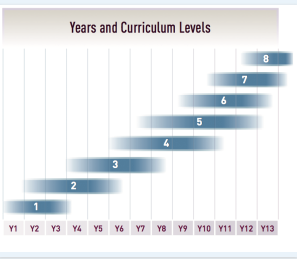

Curricular Levels: There are 13 grades, from 1-13 (similar to our K-12), in New Zealand. From what I understand, students can enroll at the point they turn five (compulsory education starts at age 6) with what seems to be rolling admissions. Rather than have 13 curricular grade levels, one for each year of school as we have in the U.S. state standards, the New Zealand Curriculum for English-medium schools has 8 curricular levels. (There are two curriculum that make up the National Curriculum outlining the expectations for learning and teaching. Te Marautanga o Aotearoa is for Māori-medium schools.)

Curricular Levels: There are 13 grades, from 1-13 (similar to our K-12), in New Zealand. From what I understand, students can enroll at the point they turn five (compulsory education starts at age 6) with what seems to be rolling admissions. Rather than have 13 curricular grade levels, one for each year of school as we have in the U.S. state standards, the New Zealand Curriculum for English-medium schools has 8 curricular levels. (There are two curriculum that make up the National Curriculum outlining the expectations for learning and teaching. Te Marautanga o Aotearoa is for Māori-medium schools.)

For the first five years, these are essentially overlapping multi-year bands with the assumptions that students are in different places in their learning. In about Year 11, when students start to focus on the NCEA, the curricular levels are organized more closely around one-year bands.

The NZ Curriculum identifies academic domains. It starts with what is the domain, why it is important, the structure of the domain, and the achievement objectives for each curricular level. These are higher granularity than the American state standards. In fact, several educators in primary schools said that even though the testing and the labeling of students was in conflict with the principles and values outlined in the NZ Curriculum, it was helpful to build greater capacity around the more precise skills and knowledge students needed to develop in order to successfully master the achievement objectives.

NCEA Levels: The National Certificate of Educational Achievement levels indicate three different performance levels that students earn during their secondary years. I’ll be writing more about NCEA tomorrow, but for now you just need to understand that students earn credits by demonstrating that they are at a minimum proficiency in an achievement objective. If they earn enough of the right mix of credits, they are awarded the certificate for either Level 1, 2, or 3. Students must achieve NCEA Level 3 and the University Entrance requirements for particular programs in order to apply for admission. For example, students seeking to pursue a college degree in engineering must take external assessments to demonstrate mastery in order to apply for admission to university. Thus, you can often see remains of a more traditional system within schools serving higher income students who seek to go to top-tier universities.

Although most secondary schools have organized themselves so that students focus on earning Level 1 in Year 11, Level 2 in Year 12, and Level 3 in Year 13, there is nothing inherent in the NCEA policies, managed by the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA), that requires it to be sequentially structured. Students can earn Level 2 without earning Level 1, Level 3 without Level 2. A few high schools are venturing down the path of focusing on helping students to focus on “quality credits” that lead directing to Level 2.

For Americans, it isn’t easy to grasp that the NCEA levels are not the same as a diploma. Although we grant a diploma to every student who completes high schools (and, in some states, passes a graduation exam), it doesn’t mean that every student knows the same thing. We value the equality of everyone getting a diploma even though it is relatively meaningless in terms of what a student is prepared for or the opportunities it opens upon graduation. New Zealand has constructed a system in which the secondary school certificate is part of the adult or tertiary system. A bus driver enthused about NCEA because the levels were part of the tertiary system of higher education and training providers. “I got to Level 1. It’s great, I can continue on to Level 2 whenever I want.” The NCEA has been constructed to intersect with university as well as vocational pathways.

New Zealand certainly wants to increase the number of people receiving a certificate of achievement and the number of students receiving Level 2 and 3. It also cares deeply about improving educational attainment for Māori and Pasifika students. Although there is a strong concern about equity, there also appears to be a general comfort among educators with the idea that students enter with different knowledge and skills and that they will therefore leave school with different levels of achievement. I only met two educators who were thinking about how they could accelerate learning or structure more time for learning so that students who enter at lower curricular levels could still compete for Level 2 and 3. Most secondary educators looked entirely surprised at the idea of adding an additional year for students who had entered at lower curricular levels but aspired to reaching Level 2 or 3 certificates of achievement.

Comparison of the Three Performance Levels: Curricular, NCEA, NZQA

(adapted from the report Comparison of Senior Secondary School Qualifications)

NZQA Qualifications Framework: New Zealand established the New Zealand Qualifications Authority to manage credentialing of learning and skills in the tertiary (post-secondary education and training) system. The New Zealand Qualifications Framework is organized around six levels of certificates and diplomas.

The NZQA plays several critical roles, of which I will highlight two. First, NZQA manages the National Certificate of Educational Achievement described above. It offers resources about the assessment specifications for each of the three levels for each subject as well as resources regarding both external and internal assessments. It plays a critical role in managing the external assessment examinations (except for the IB and Cambridge exams) and moderating the internal assessments. It was not always so. In the early implementation of the NCEA, a mid-course correction was required to build a much stronger moderation mechanism in response to high variability in credentialing credits. This moderating capacity contributes to the ‘competency-based’ characteristics the NZ education system as there is a high degree of reliability across schools of what it means for secondary students to earn Level 1, 2, or 3.

The other critical functions that NZQA plays is to approve tertiary programs that result in certificates and diplomas and to ensure consistency of expectations within the six levels to ensure that students will build the skills, knowledge, and attributes upon completion of the qualification. Thus, they play a critical role by stewarding a policy structure across the intersection of employers, workforce development, tertiary providers, and secondary schools. Interestingly, even without Andrew Carnegie shaping their culture and education system, the qualification system is still based on a credit system that draws on a learning hours based on:

- direct contact time with teachers and trainers (‘directed learning’)

- time spent in studying, doing assignments, and undertaking practical tasks (‘self-directed’)

- time spent in assessment

The fact that time is still used as a proxy of learning, even in a system that is designed around knowing that students learn differently, indicates how entrenched our understanding of time is in our culture.

Although I traveled to NZ believing that this alignment of the system would mean that there would be a seamlessness between the secondary and higher education sectors, I found that this was not altogether true. First, the competitiveness of the college admissions process has placed demands on the secondary system to provide information for the colleges and universities to rank and sort. Much better than the American system of the high schools playing this function with the problematic GPA, the New Zealand grading system in secondary school (yes, a national grading system) has been shaped by the demands of universities to have clear-cut scores to determine one of four levels of achievement: Not Achieved; Achievement; Achievement with Merit; Achievement with Excellence. This pressure to achieve at the highest levels on top of the demand to earn certain numbers and mix of credits to reach Level 1, 2, and 3 in the final years of secondary school has placed the focus on “chasing credits” rather than extended, deeper learning. Thus, the tertiary demand to rank and sort students is undermining the efforts of the National Curriculum to establish modern pedagogies based on the research on learning.

Second, I assumed that the problem of college remediation that haunts the American education system would be minimal. Certainly, the problem isn’t as extensive as in the U.S. However, a governmental staff person did suggest that there were gaps between the secondary and tertiary sectors that students might fall into. It’s possible that this is because more students are earning certificates during secondary school or that some students pursue Level 2 and 3 while in college rather than earning them during secondary school. However, further investigation is needed to understand what is driving this emerging problem.

How Might We Move Towards a Seamless Multi-Sector System

In the book Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education, Principle #12 is Maximize Transparency. When schools design with transparency in mind they can empower students to own their education. Students know exactly what the learning targets are, what proficiency looks like, and what they need to do to successfully learn. Most schools transitioning from the opaque traditional system with its mixed messages and false signals take some time to create (although some just use state standards for the interim) a transparent framework of learning objectives. This is often referred to as a competency framework that identifies the academic knowledge and skills as well as the dispositions, skills, and mindsets that students need to be successful learners.

The problem is that schools are often creating their competency frameworks and what it means to be proficient independently. If the entire district is moving toward competency education, then there is the opportunity to create an aligned framework that clarifies expectations from K-12. However, it is difficult to engage our institutions of higher education and training in the level of collaboration we would need to create a seamless system that makes it perfectly clear what the expectations are for entering a non-competitive college, community college, elite college, or technical program.

There is work underway in the world of higher education and workforce development to create a more transparent and flexible system. Connecting Credentials offers the best hope for creating a mechanism for districts and institutions of higher education and employers to manage the complex intersection of the three sectors in ways that are transparent to students and job seekers. Other parts of this system-building effort, much of it funded by the Lumina Foundation, include badging, credentialing, new information/data systems that provide more accurate and up-to-date information for job-seekers, post-secondary education/training and employers, and competency-based post-secondary programs.

Much of this work in developing a modern post-secondary/workforce development system in the U.S. is being done without consultation of the K-12 system. This is a horrendous mistake. Although one has to carve the boundaries of any broad-reaching initiative at some point, the failure of our post-secondary institutions to think about their impact on K-12 is likely to be an equally far-reaching mistake. Instead of thinking of higher education as a provider to employers, we need leaders at all levels of colleges and universities to understand the tremendous impact they have on shaping K-12 systems. Instead of thinking of linear lines of a supply chain, a trait of Western culture, perhaps we might embrace some of the values of Māori culture that emphasize reciprocity in relationship building; the well-being of the full community, not just the individual organization; and stewardship.

Each of us, and each of our organizations, are in the middle of a web of relationships, systems, and networks. There is no beginning. There is no final step. We need our higher education partners to understand this and participate as true allies in thinking about how the choices and policies they make impact the behavior of K-12 systems and our society’s goals for raising achievement and reducing inequity. Together, we can redesign our education and workforce development systems to be more flexible, more responsive, more cost-effective, and adaptive enough to respond to the economic changes that are tumbling toward us.

This article is adapted and updated from the original blog published at CompetencyWorks in December 2018.