“One of the biggest benefits of mastery-based learning is the clarity for teachers. We have had so many good conversations with teachers about what they are teaching, what they want students to be able to know and be able to do, and why they are teaching it. We know we are doing a good job at implementation, as it is making alignment a natural process. The selection of activities are more likely to be based on the skills students need and what students need to practice. There is more focus on what students need to do to learn something rather than simply covering the content.”

– Greg Baldwin, Principal, New Haven Academy, CT, 2016

Description

Coherent systems align all of their parts around a common purpose and vision for student learning. A report, Alignment in Complex Education Systems: Achieving Balance and Coherence, by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) describes how the majority of developed countries around the globe build alignment of three areas of their education systems: defining the knowledge and skills students need to know and be able to do at progressive stages through graduation, creating curricular frameworks that illustrate the competencies and learning objectives in standards and measuring learning and attainment through student assessments and school evaluations. The OECD reports, “If these systems are misaligned, it is impossible to draw valid conclusions about the success of student learning or to develop effective strategies for school improvement.”

Coherence is the result of intentional design: districts, schools and educators are deliberate in aligning every part of their system, school and classroom. The process of alignment of school design, instruction, assessment and learning experiences is well-managed, recognizing that with alignment comes changes in policies, practice and the capacity of staff to implement with fidelity. There is a clear rationale for each decision point in design, implementation and continuous improvement. Intentional design is thoughtful about the sequence and pace of the implementation process so that staff have opportunities to build capacity as needed. Alignment is not something that is done in one fell swoop. It is a step-by-step process of refinement and sometimes innovation. The best change strategies embody the values and beliefs of the competency-based system to build trust, individual learning and organizational knowledge

Key Characteristics

- Purpose-driven. Districts and schools begin alignment with the the purpose of ensuring each and every student is fully prepared for college, career and life. The graduate profile emphasizing academic knowledge, transferable skills, and the skills for lifelong learning drive decisions. There is shared understanding that all decisions should come back to our central mission.

- Student-centered. The purpose to ensure every student is mastering knowledge and skills places students and what it takes to help them learn at the core of the alignment process.

- Common learning framework. A transparent learning framework is developed and used to align instruction and assessment. Furthermore, the learning framework and what proficiency looks like at each performance level is available to students and families.

- On-going alignment processes. Processes are in place to ensure ongoing processes of alignment and that the school and district systems support an aligned instruction, assessment and learning experiences (curriculum). Leaders manage implementation so that educators have opportunity to pursue personalized professional learning to build their skills to implement an aligned system. Educators draw on collaborative processes to help fine-tune the design of learning experiences to ensure that in addition to building academic knowledge, students will have the opportunity to develop building blocks of learning and higher-order skills.

- Clarity and capacity. Instructional, operational and structural systems only matter if people understand them, understand their roles and actually know what to do. Competency-based systems provide the balance of detail and simplicity—so called “elegance”—that enables people at all levels to actually know what they are supposed to do. Resources are provided to support educators in building the knowledge and skills needed.

- Improvement. Continuous improvement processes take into consideration the interdependence of an aligned system. As improvements are considered, alignment is maintained by asking, “if we change x, what will it mean for y?”

How Is Seeking Intentionality and Alignment Important for Quality?

Creating a high-quality school and system doesn’t occur by happenstance. It requires intentional effort to align the culture, structure and pedagogy around three things: purpose, students and strategies that will lead to reaching the purpose. Intentionality is an ongoing creative design process that empowers people to have the ability to change and improve their environments. When intentionality is a feature of a district and school, leaders, teachers and even students are part of an ongoing process to create and improve the school. Intentional design creates and is created by a strong collaborative culture of learning and a sense of urgency.

Alignment Around What?

Alignment is the process of making sure all the pieces fit together to create a coherent structure that will support learning. But alignment around what? Alignment begins with the shared purpose and desired outcomes. Usually this is the graduate profile and definition of student success. When systems align around the goal of students being able to apply their knowledge and be independent learners, there are clear implications for learning and teaching. Alignment also takes into consideration the student population. Districts, schools and teachers to get to know their current students, asking many of the following questions. What is the culture of their families and communities? What has been their educational experience so far? Districts and schools experiencing demographic changes in their communities will find that they need to be more adaptive and possibly develop new capacities to align with their students. Schools are designed to support relationship building so that teachers are better able to know their students. Teachers take into consideration what students know and can do, their social and emotional skills, and the things they care most about in meeting students where they are.

The final focal point of alignment is the set of strategies determined to best help students learn and succeed, which are shaped by learning sciences and equity. Districts, schools and educators will want to turn to the research on the science of learning to shape policies, schools design and instruction. They will also want to draw from the research on equitable strategies that have been developed to ensure historically underserved populations reach high levels of achievement. This doesn’t always mean integration of strategies: it may also require ending inequitable practices.

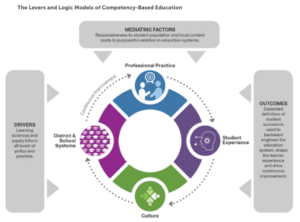

In the paper Levers and Logic Models: A Framework to Guide Research and Design of High-Quality Competency-Based Education Systems, four logic models are outlined to identify the elements of culture, student learning experience, professional practice, district and school systems. As depicted in the figure below, these logic models must be aligned within the levers of desired student outcomes, mediating factors of local context and student population and the drivers of the learning sciences and equity strategies.

The Common Learning Framework

Districts and schools develop a central learning architecture or common framework that clarifies what is expected for students to know and do at each performance level or grade level to which instruction and assessment are then aligned. In most cases, performance levels are the same as grade levels, although some districts have established unique performance levels. This common learning framework may be organized around higher level competencies and the standards that contribute to each. However, many districts begin with the state standards with which they are already comfortable and introduce competencies at a later point in implementation. The value of beginning with competencies are two-fold: 1) competencies demand rigorous deeper learning instruction and assessment and 2) competencies can reinforce a sense of purpose and make connections for students about why it is important to reach proficiency on standards. Once the learning framework has been agreed upon it may be translated into more student-friendly language.

Clarity and Consistency

A critically important step in alignment is the process of building a shared understanding of what it means to be proficient in each of these competencies and standards at each performance level. The processes of building consistency through moderation and calibration catalyzes the collaborative professional learning of teachers. By looking at student work and discussing the features that indicate proficiency at different performance levels, teachers begin to think more deeply about the instruction and assessment needed to help students master the learning targets.

Aligning Instruction and Assessment

Every high-quality school aligns instruction, curriculum or what we refer to as learning experiences, and assessment. However, competency-based education is intentional about also considering the definition of student success included in the purpose and the student population. Thus, the structures that support instruction, learning experiences and assessment need to have the following capacities: able to respond to students where they are including above or below grade level, designed to help students build the lifelong learning skills and aligned with higher-order skills.

Aligning Professional Learning

Aligning instruction and assessment tends to trigger increased attention to professional learning for educators. For those schools that include clarifying the pedagogical principles and fully embedding learning sciences into instruction and assessment in the early stages of implementation, the process of aligning the capacity of the educator workforce is a natural step. Those schools that begin with creating a common learning framework are likely to discover substantial areas of misalignment between learning objectives, assessment, instruction and curriculum. This may require sequencing capacity-building across the school as well as supporting individual teacher’s professional growth. Teacher professional learning, based on where teachers are in their own skill development and the stage of development of the competency-based system, is likely to focus on how to support students in developing the building blocks of learning, classroom management for personalized learning, instruction for the development of higher-order skills and deepening content instruction and assessment literacy.

Aligning School Design and Operations

Districts and schools will often find that they need to rethink schedules for more applied learning, expand community partnership for offering real-world problem-solving and building capacity for performance-based assessment. Schools may also want to develop or extend the array of wraparound services that students can access.

Opportunity for Broader Systemic Alignment

Although it is beyond the scope of this publication, there are opportunities to align competency-based structures between K-12 and postsecondary institutions—colleges, universities, training and employers—to create more transparent and meaningful credentials. Quality requires intentionality and alignment: every aspect of cultural, instructional and operational systems must support student learning, student success and the vision driving the district or school. Like a complex machine, all parts of a quality system work in concert to produce desired outcomes. Furthermore, all people in the system must understand their part in the coordinated effort to produce desired outcomes: their role, the needed capacities, and their connection to the other parts. Finally, the system must maintain this focus and alignment through the critical processes of continuous improvement—as people and parts adapt to meet students’ needs, systems must learn to manage and integrate these micro changes into the larger whole.

Policies and Practices to Look For

- Measures of student outcomes are well articulated, including how equity in outcomes is being measured. The outcomes or graduate profile clearly explains the knowledge and skills students should learn accompanied by examples of student work to clearly indicate performance expectations.

- A common learning framework is well-developed and teachers are knowledgeable with instruction for the level above and below the grade level they teach.

- Teachers have opportunity to experiment and innovate in pursuit of greater alignment.

- Teachers have opportunity to plan, collaborate and learn. Professional learning communities are supported and nurtured.

- School designs, learning experiences and professional learning opportunities for educators are based on outcomes and informed by data on student learning.

- Districts and schools adapt or redesign structures to support the development of outcomes and the strategies used to help students reach them.

- Learning experiences are designed to provide opportunities for students to strengthen their social and emotional skills.

- Instruction and systems of assessments support application of skills and development of higher-order skills. Districts and schools build capacity for performance-based assessment and assessment literacy.

Examples of Red Flags

![]() Graduate profile emphasizes deeper learning and higher-order skills but curriculum, instruction and assessments are primarily set at memorization and comprehension. As districts begin the process of aligning instruction and assessment to the common learning framework of competencies and standards, they often discover that instruction and assessment are not aligned with the depth of knowledge of the standards. They soon begin to make adjustments to have more applied learning opportunities, performance tasks and performance-based assessments.

Graduate profile emphasizes deeper learning and higher-order skills but curriculum, instruction and assessments are primarily set at memorization and comprehension. As districts begin the process of aligning instruction and assessment to the common learning framework of competencies and standards, they often discover that instruction and assessment are not aligned with the depth of knowledge of the standards. They soon begin to make adjustments to have more applied learning opportunities, performance tasks and performance-based assessments.

![]() The school knows that many students are entering at levels several years below age-based grade level but continues to emphasize delivery of grade-level instruction. Alignment isn’t just between standards, instruction and assessment. It involves aligning with the student population as well. In early implementation stages, districts often use the semester as a beginning point of monitoring learning with all students expected to master the learning objectives by or soon after the end of the course. This is unlikely to be achieved if students have multi-year gaps in their knowledge. Although schools use different strategies to meet the needs of students with gaps they may continue to pass students on to the next course without developing long-term strategies to address gaps. The failure to have honest conversations with students about the level they are performing does a disservice to students. They will never know what is really expected until they are forced to take remediation courses at college. Thus, districts and schools need to invest in long-term strategies that truly meet students where they are and help them to reach graduation competencies.

The school knows that many students are entering at levels several years below age-based grade level but continues to emphasize delivery of grade-level instruction. Alignment isn’t just between standards, instruction and assessment. It involves aligning with the student population as well. In early implementation stages, districts often use the semester as a beginning point of monitoring learning with all students expected to master the learning objectives by or soon after the end of the course. This is unlikely to be achieved if students have multi-year gaps in their knowledge. Although schools use different strategies to meet the needs of students with gaps they may continue to pass students on to the next course without developing long-term strategies to address gaps. The failure to have honest conversations with students about the level they are performing does a disservice to students. They will never know what is really expected until they are forced to take remediation courses at college. Thus, districts and schools need to invest in long-term strategies that truly meet students where they are and help them to reach graduation competencies.

Source: Sturgis, C. & Casey K. (2018). Quality principles for competency-based education. Vienna, VA: iNACOL. Content in this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 international license.