The following is the keynote at IMS Global Digital Credentials Summit.

In some ways, we are all here because we are stewards of our future. We are here — K12, higher ed, workforce development, employers — because we are all engaged in modernizing our education system and the overall workforce development system. We want to optimize learning, we want reliability of credentialing of that learning, and we want to make sure that students can develop the knowledge and skills that are going to open doors and create opportunity in their next stage of life.

As I was prepping for this meeting, I started to wonder, What would Andrew Carnegie think if he was able to join us at this meeting? Now, if you don’t know about Andrew Carnegie and his role in shaping our education system, let me quickly tell you the story. Andrew was an immigrant from Scotland and came to be one of the richest men by building the steel industry. He thought it was a travesty to have such a fortune upon his death, thus became an active philanthropist with a strong focus on education including creating our library system.

Now let’s think about what was happening around the turn of the nineteenth century. Everything was changing in the U.S. Thousand of immigrants arrived each day. Schools were expanding to educate and assimilate them — and teach them to be compliant. (Remember, there were also a lot of ideas about revolution floating around as well as a growing demand for factory workers.) The education system was quite ill-defined. There were all types of ways of organizing curriculum. There wasn’t a clear difference between high school and college. It was a bit of free-for-all. The National Education Association’s Committee of Ten was deciding what the high school curriculum should look like including what courses should be taught in what order. The College Board began to offer examinations for each of these courses.

One of the things Andrew invested in is expanding higher education. In 1905 he decided he wanted to establish a pension program for college faculty. So the first thing they had to figure out was what a college was. They decided a college had to have at least six professors and a course of four full years of liberal arts and sciences. But then they also added that a college admissions requirements had to be at least four years of high school preparation.

But four years wasn’t going to work – students might go once a week. So now a definition of a college included the admissions requirement that students complete fourteen courses based on daily classes totaling 120 hours of instruction. This became known as the Carnegie unit. For higher education, there was a slightly different formula. (See The Carnegie Unit: A Century Old Standard in a Changing Education Landscape)

The Carnegie unit quickly became the currency of the education system. Academic calendars, degree programs, school schedules, financial aid, faculty workloads were all based on the Carnegie unit.

Let’s fast forward one hundred and some years. This very same Carnegie unit that was devised to help determine faculty pension, then became a profound innovation that catalyzed the expansion of our education system has ended up 100 years later as a barrier to educational innovation. Even in the states advancing competency education, completion of courses to earn credits are still required for high school graduation. The Carnegie unit is so embedded in the administration and financing of higher education it’s proving incredibly difficult to imagine life without it.

So let’s think about it — in trying to solve a discrete problem related to higher education, education leaders created a solution that had huge implications for secondary school. In designing a pension for college faculty, high school became four years and courses became 120 hours. They had other options — they could have said a college only accepts students with certain scores on the college examinations. But they didn’t say that. They chose time as the proxy for learning.

So here we are today with a Carnegie unit that has become a proxy, and a very weak proxy, for what people know.

There is an important lesson to be learned from this story for all of us: When we think about system building or redesign, even the smallest decisions may have tremendous impact on other segments of the system, way down or way up the line. If the Carnegie unit can be a powerful innovation at one point in time and later becoming an equally powerful barrier to innovation, what might be the implications of the system-building and redesign efforts going on today for the future of education?

So, what might Andrew think if he joined us here today? What might he say if knew that the unit of learning that carries his name would end up 100 years later as a barrier to educational innovation? Would Andrew have gone ahead with the plan if he knew that by standardizing the unit of learning based on time, it would create high levels of variability, emphasize coverage of curriculum over learning, and contribute to a system of education that reinforced low achievement and inequity?

The Leaky Pipeline

Actually, I think Andrew and his buddies would have gone ahead. This was the time of scientific management and a love of efficiency. The Carnegie unit and the standardization of the delivery of instruction, as if education was the same as a factory, made perfect sense to them. The irony is that as the goals of our education system changed, the system become tremendously inefficient. We think of it now as a leaky pipeline.

Just think about the adage, “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” The system was highly effective in doing what it was designed to do in the first half of the 1900s. The original education system was designed to provide basic education to the wave of new immigrants seeking safety and economic opportunity in the U.S.; vocational education for pathways into factories; and ranking and sorting students based on their grade point average to determine which students would go on to a college education to take their place in the academy, at the head of organizations, and in political leadership.

But things started to change. The civil rights movement took hold and we are increasingly embracing our common humanity rather than believing that there are differences based on our gender, race, and class. We now want everyone to have a high quality education that provides equity in access and opportunity. Add on the fact that what we want students to know and be able to do is changing and expanding along with the changes in technology and the economy…and the result is the traditional education system just isn’t up to the job. Students are not getting the education they need.

We’ve tried to fix the leaks with a zillion different programs. Over time, and it’s taken us a while, we’ve come to understand that it isn’t worth trying to patch the leaks. We need to redesign the pipeline itself. And that is why we are all gathered here today.

Actually, we really can’t blame Andrew and his mates too much. It’s hard to measure learning and, at the time, much less was known about learning than there is today. And there were strong beliefs shaping what they saw as options.

There were beliefs that some people couldn’t learn. There was a belief that some people were smarter than others and there was little to be done about it. It was okay to have instruction only delivered through lecture because some students were going to learn it and others weren’t.

There were also beliefs that some people shouldn’t learn based on gender, race and culture, and class.

There were also a different set of belifs about motivation. As this quote from Andrew Carnegie suggests, motivation was something that the individual had or didn’t have. They thought only about extrinsic motivation — carrots and sticks. They didn’t think about the power of the context — in which people learn and earn — to shape their motivation. They didn’t understand that children, teens, and adults can learn to manage their motivation, their minds, and their emotions to be powerful learners.

Today, we have an enormous body of research on learning and development. Some of this research is on cognition and how the brain processes information. Some of this research is on the psychological and social factors that shape learning.

Daniel Pink, in his book Drive, reviews the research about motivation and the implications for the workplace and schools. Intrinsic motivation is proving to get much better long-term outcomes than extrinsic motivation. And what motivates people is autonomy, mastery and purpose. Thus, how we shape our institutions and organizations will impact motivation for people of all ages.

We now know that students are not empty vessels to be filled by faculty lecturing. We know that students need to be active learners, and the better they understand how to learn and how to manage their own mind and emotions as part of that process, the more effort they can put into their learning. The trick is to create the conditions that motivate them to develop the skills to be lifelong learners.

The lesson for all of us is to think about how the broader systems that support K12 and higher education contribute to unleashing motivation…or to undermining it. As we redesign the system we need to remember that the context of learning truly matters.

Our vision for a system linking K-12, higher education, the labor market and a cycle of career development means that we need to move well beyond the time-based proxy of learning that the Carnegie unit offers. We want a K-16-Career-Economic Driving Eco-System that ensures students are learning and that they can apply what they are learning — call it competency based, mastery based, or proficiency based. We are redesigning the education system to optimize learning, to create opportunity, to be reliable, and to enable flexibility in how schools are designed and how learning takes place.

But this is a huge vision! And so many pieces of the puzzle to consider and the implications of those pieces.

How do we not make the same mistakes Andrew and his mates made?

I propose that to fully redesign this system, we are going to have to do three things:

- Build Common Language

- Agree on Common Design Principles

- Build Commonly Shared Commitment to Each Other and to Equity

We need to be able to talk and understand each other. Otherwise, we stay in the muddle of understanding the “what” rather than jumping into the much more important creative process of the “how” we are going to design our future.

In general when you look at the definitions of CBE in higher education as compared to K-12, they are very similar. I drew out several common concepts from CompetencyWorks and from CBEN on this slide. I don’t think anyone will be surprised by these.

However, as you dig deeper there are variations:

- In higher education, CBE tends to be programmatic, whereas in K12, the assumption is that CBE won’t work effectively unless it is introduced schoolwide and hopefully district-wide.

- In higher education, you have more control over which students enter into a program based on their prior learning and their lifelong learning skills, whereas K12 has to meet students where they are even if that means four, five, or six years behind where they are expected to be.

- Higher education focuses on marketable skills, whereas K12 is focused on very broad sets of knowledge and skills. In fact, we get immediate pushback from communities if we emphasize skills too much.

- Finally, higher education focuses more on creating opportunity and access for students, whereas in K12, the focus is on equity in which the system should be designed for every student to be successful.

We are going to need language to help us talk about the segments of the education-career development pathway.

If we are going to be able to have powerful conversations about how aspects of system design will impact learners and organizations at earlier and later parts of the system, we need to understand what is happening in each of those segments.

Right now, we generally talk about it in terms of institutional sectors. Or is there another way to segment the pipeline that opens up more creativity and understanding? Here is an example that is thinking more about the developmental stages. Maybe there are others that would help us think more strategically.

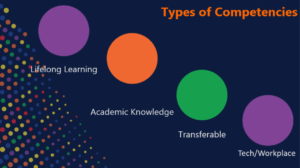

One of the things we are going to need to make sense of is the different types of competencies. Right now, we are in a period of competency generation.

In the adult systems, the emphasis is on building an opportunity eco-system that is based upon a common currency around skills and competencies.

However, in the K12 system, there is an emphasis on academic knowledge, the skills to apply it, and lifelong learning skills. We haven’t done a good job in including the skills developed in career tech programs, so we definitely need a mid-course correction.

We also are going to have to find or create language that can allow us to talk about the granularity of the learning objectives and how they might stack into higher level competencies across sectors. We are going to want to be able to talk about how badges that are developed during adolescence in after school programs might stack up toward high school or college level credit. We will want to be able to understand how high school competencies relate to college level competencies and to job-specific competencies. I’ll return to this in a few minutes.

One of the areas that the American system is terribly weak is on the issue of consistency and transparency. For some reason, we tolerate enormous levels of variability so that a high school diploma doesn’t even guarantee that a student can read and write at ninth grade levels. The variability creates distrust throughout the system, with employers frustrated that students don’t have the skills they need, higher education needing to create remediation programs, and students bearing the cost of credentials that don’t always lead anywhere.

What we need is a system that calibrates across the sectors. I had the opportunity to visit Aotearoa New Zealand last fall, and what you see here are examples of their efforts to create reliability in their system. It’s certainly not perfect. They have a curriculum framework for years 1-8 with the assumption that not everyone is at the same place. They have a system of credentialing called the National Certificate of Educational Achievement for the intersection of secondary school, high education, and entry into the labor market, which is highly calibrated and highly transparent so that students, parents, teachers, and the university system have the same expectations. This system of credentialing is able to cross-walk across the knowledge and skills needed for college admissions and those for employment. The system works because there is an agency, the NZ Qualifications Authority, that is dedicated to making sure there is consistency in their credential system.

There is substantial design and system-building work going on in each of the sectors. I wouldn’t call them silos exactly, but there is very limited collaboration across K12, higher ed, workforce development, and employers.

Each of us are developing design principles or quality principles – and there is overlap but there are also differences.

Could we strengthen our efforts by understanding each other’s design principles and even creating a common set for system-building?

In K12, we’ve identified that it is imperative that one of the drivers for schools and for the system is the research on learning and development. Everything should be organized based on the research so we can optimize learning for students and how we design professional learning for teachers.

The Committee of Ten selected a strategy that wanted to make things easy for teachers. We want strategies to help students learn. And we want strategies that provide teachers with the feedback and support they need to develop their overall knowledge of teaching, assessing, learning, and development.

While I was at CompetencyWorks, we identified 16 quality design principles for K12 CBE with the input of about 100 practitioners and researchers from across the country. They are organized into culture, teaching and learning, and structure.

CBEN also created a quality framework.

There are several areas that overlap with K12, such as:

- Intentionality

- Alignment

- Continuous Improvement

There are also differences, which may be differences in emphasis only:

- K12 emphasizes a culture of inclusivity — students and adults in the system need to feel respected and a sense of belonging. Feeling safe creates the conditions for learning.

- It also emphasizes instruction that is aligned with the research on learning and development, including very strong emphasis on assessment for learning.

These different types of design and quality principles are shaping the ways districts and schools colleges and universities are creating competency-based approaches.

Design principles are also informing system-building efforts.

Here we see the design principles used by IMS Global in developing digital credentials: learner-controlled, skills-based, verifiable, shareable and discoverable, and interoperable.

Truly, the adult side of the system has been doing PHENOMENAL work in building out the infrastructure of a new system with new functionality.

IMS Global is helping to creating the credential infrastructure for learners, including the comprehensive learner record, digital credentials, and the CASE Network to map competency frameworks.

There are also many new efforts underway.

- The NESSC has been building agreements with college admissions officers, what I refer to as the proficiency pledge, to recognize proficiency-based transcripts so that parents and students do not bear any risk from the innovation.

- Mastery Transcript Consortium, now a flourishing public private partnership, is prototyping a high school transcript.

- Southern New Hampshire University and LRNG, a community-based non-profit, are creating pathways for low income youth from badging to college credits.

- Corporation for a Skilled Workforce’s Connecting Credential and Credential Engine is creating a transparent marketplace for credentials.

- IMS Global has a demonstration project, Talent Stream, to present a machine-readable link to HR talent systems via resume or application.

Are they using the same design principles? I honestly don’t know. We need to take a look.

I’ve been talking a lot. Let’s take about five minutes for all of you to talk to each other. Turn to your neighbor, or teams of three are fine as well, but keep it small.

As you think about all these different types of design principles, which ones do you think are most important within all of the sectors in creating competency-based models? Which ones are most important to strengthen the collaborative capacity for system-building across sectors?

Each of us see different problems to be solved and challenges in creating a CBE system based on our perspectives. In order for us to create a fully-aligned kindergarten through employment system, we are going to have to be willing to help solve each other’s problems.

Let’s look at two examples.

The intersection between high school and college offers examples of problems that can’t be solved by one sector or the other. Here are two:

One challenge is to figure out a way to calibrate what it means to be competent in writing at eleventh grade, twelfth grade, the first year of college, or for a career pathway job. We know completion of courses isn’t going to get us there. What needs to happen to make college readiness transparent and consistent?

As long as college readiness remains hidden, we can’t really engage in continuous improvement.

Another example is the GPA. It’s the best predictor of success in college we have, yet it doesn’t tell us what students know and can do in terms of academic skills. It tells us that students have strong habits of success. Yet, because college admissions officers depend on the GPA, it is strangling the ability of secondary schools to shift to a scoring system that is more aligned with the actual attainment of knowledge and skills.

I think there is a difference in the ultimate goals of modernizing education to a career pathway in K12 and at the upper stages of the system. Perhaps it is just different words, but I think it is more.

In the adult side of the system, higher education and workforce development, the ultimate goal is often described as creating a system of opportunity. In K12, educators turn to CBE for a number of reasons — and one of them is to create a more equitable system.

Equity for K12 means making sure every student can discover their potential and be successfully prepared for college and careers. The idea is that students have the option to follow either pathway or, what is most likely going to happen, is they will mix school and work together. It doesn’t mean every student needs to or should want to go to college. But the option should be there and the decision should rest with students.

Expanding opportunity is very important BUT equity requires us to design for success.

In K12, to design for success so that every student is discovering their potential and has the knowledge and skills to make choices about their future means that quality and equity are essentially the same thing.

In K12, a quality competency-based school or district has to also be driving toward equity. One can’t call it high quality if historically underserved students are still being underserved. Thus, quality = equity.

The key, of course, is continuous improvement both at the organizational level and at the teacher professional learning level. Assessing learning creates a triple feedback loop — it informs student learning, teacher professional learning, and organizational learning.

To reach educational equity will require us to seek out patterns of inequity. One of those sources of inequity is bias. All of us have bias, and it shows up in different ways. The problem with bias is that it clicks in so fast we don’t even know that it shaped our ideas. So the first thing we have to do is just own up to the fact that we all bring a bit of bias into our daily lives. And then second, we need each other to uncover it and shake it out.

As we think about system-building, the question is will employers, workforce development, and higher education join in with K12 to address the equity challenge? Will the system-building efforts in the adult side of the system take into account the repercussions on the K12 side?

Will we be like Andrew and his pals and design around one set of problems and design principles? Or will we make a shared commitment to quality and equity throughout the system? Will we make sure that sure that the system-building efforts result in helping K12 solve the challenge of educational equity?

Ty Cesene, a co-founder of a Bronx Arena High School in NYC, really helped me understand competency-based education when he said, “We aren’t done innovating until every student graduates.”

This is what accountability is all about.

And when — not if, but when — we are successful in reaching greater educational equity, it will have huge impact throughout the system. For example, in the future, when we are reaching greater educational equity, this room will reflect all the beautiful diversity of America.

Andrew and his mates had it easy. They were designing a brand new education system. They had plenty of white space.

Our challenge today is much more complicated, as we are trying to redesign a firmly entrenched system. However, we have better tools than they did. We know so much more about how people learn and about how systems operate. We know collaboration is absolutely essential to discover sustainable solutions. And of course we have a lot of new technology in our pockets.

But redesign is definitely more complicated and it will require different types of leadership strategies:

- At times, we are going to have to deconstruct some of the functionality of current organizations and consider different roles. At times, we are going to need to stop doing some things in order to make room for new things.

- This is likely to trigger emotions. We’ll need to be kind to each other as some grieve letting go of things that they like to do and others get nervous as they step into that awkward space of learning how to do new things. And we aren’t going to get it right the first time.

- And it will require us to build our capacity for distributed leadership strategies because the full education and human capital system is a puzzle far more complex than any one person or any one organization can manage. We are always going to need to pull together a broad set of perspectives to understand implications and see opportunities.

To wrap us up…Andrew Carnegie was a very complex man. He was very serious. And he was very driven.

And he also knew that laughter and joy are the secret ingredients for success.

So let’s go out there and have us some fun over the next two days at the IMS Global Digital Credential Summit.