The series on Aotearoa New Zealand continues here with a look at Hobsonville Point Secondary School.

Co-construction, connection, and collaboration are the name of the game at Hobsonville Point Secondary School (HPSS) in Auckland. Oh, and I’d add one more – challenging convention. HPSS is designing learning experiences for students taking advantage of the flexibility offered by New Zealand’s National Certification of Educational Achievement policies. It’s an inspirational story that may inspire American educators and policymakers to consider what is possible within the flexibility offered under ESSA.

Background

HPSS is designed to serve Years 9-13 (similar to grades 8-12 in the U.S.) and is in its fifth year of operation with 550 students. The New Zealand Ministry of Education has strategically responded to growth in student populations by creating new schools designed with modern pedagogy and modern learning environments. The new schools have much more open, flexible space than traditional schools. HPSS is considered decile 10 school. In other words, it serves students from higher socioeconomic families. However, this doesn’t mean that HPSS doesn’t have to be prepared to serve incoming students with a range of skills stretching from Curriculum Level 2 through 6. Similar to schools across New Zealand, HPSS starts with the understanding that students are going to be at different points in their learning.

Designing a Modern School

Launching a new school, one with a modern architectural design and a modern pedagogy, is a big lift. After being hired by the board (NZ Tomorrow’s School policy established 2,500+ autonomous schools run by a board of trustees), primarily community members, Maurie Abraham, principal of HPSS, brought together a senior leadership team and started the process of clarifying the vision, values, and design.

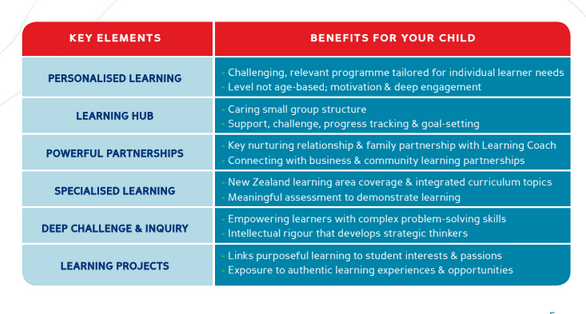

Abraham knew from his previous experiences in a Māori community that Hobsonville needed to start with attending to students’ well-being and “lifting their engagement and motivation.” Learning Hubs, similar to advisory in the U.S., provide time for students to work with learning coaches on habits and dispositions. He also knew it was critically important to pay attention to pedagogy, explaining, “If you don’t make a change to the teaching, no matter what else you do, the outcomes are going to be the same.” The team also thought through their values and how they would be embodied in the school culture. They thought through how they would work together, the purpose and protocols of meetings, what timetables (schedules) would look like, the curricular design, and the experiences they wanted for students.

By empowering themselves to design what they thought would work for students, the staff also empowered themselves to question conventions. This meant they often had to find new ways to meet objectives. Abraham emphasized that the mindsets of the staff are important. “Too often we have visitors who look at our model and quickly dismiss it by saying ‘oh our timetables won’t let us do that’ rather than asking themselves how might they introduce new practices that were more effective for students.”

See Prospectus for an in-depth explanation of the school design.